Tell me about your dreams

As a student of psychology, the first question that people often ask me is: “Can you tell me

what’s the meaning of that dream I made last day?”

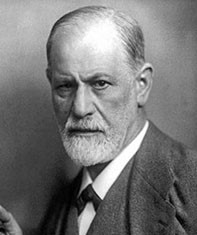

I get it! Psychology is often associated with Freud, the father of psychoanalysis and the

first to formulate a theory of dream interpretation, but dreams are only a small part

treated in a psychoanalytic setting.

Starting from the beginning, Freud (1900)

explains that sources of dreams include stimuli from the external world, subjective

experiences, organic stimuli within the body, and mental activities during sleep.

For instance, empirical evidence (Zhang,

2016) supported that memory

consolidation, emotion regulation and reception of external stimuli can contribute to dream

content.

Starting from the beginning, Freud (1900)

explains that sources of dreams include stimuli from the external world, subjective

experiences, organic stimuli within the body, and mental activities during sleep.

For instance, empirical evidence (Zhang,

2016) supported that memory

consolidation, emotion regulation and reception of external stimuli can contribute to dream

content.

Freud suggested that some connection between real life and dreams are not random, but

constrained by one’s unconscious desires. Along these lines, the interpretation of dreams

can help understand the unconscious, which try to emerge in our sleep.

This conception about dreams, as a way for the unconscious to bypass the consciousness and

express inadmissible desires, has dominated for more than half a century.

Bion (1962a, 1992b) did a revolution and took into consideration just the psychic

phenomenon of dreaming

rather that the dream as an unconscious content to be deciphered. He was concerned more with

the way we dream than with the dream’s symbolic content.

Bion (1962a, 1992b) did a revolution and took into consideration just the psychic

phenomenon of dreaming

rather that the dream as an unconscious content to be deciphered. He was concerned more with

the way we dream than with the dream’s symbolic content.

He described the dream as an essential function of the human mind: a result of a

transformation from what he called beta element, the very first sensory matrix on which

thought develops, into alpha element, which resemble the visual images with which we are

familiar in dreams.

According to this idea, the alpha function promotes the growth of thoughts; it produces

alpha elements, suitable for use in dream-thinking and waking-unconscious thinking.

In fact, he interprets dreaming as the unconscious processing of emotional experience, which

occurs continuously and simultaneously with conscious thinking: both when we are awake and

asleep. During sleep, the dream takes advantage of the suspension of consciousness, the

dream activity makes possible those emotional experiences that could not be reached in the

waking state. Bion hypothesizes the existence of a dream function that is also active in the

waking state, even though shielded by perceptions and distractions operated in reality.

With Bion, the dream is released from the state of consciousness and no longer needs sleep

to exist.

The patient would take the dream into analysis in the hope of receiving the analyst’s help

in

completing the unconscious intolerable work, but dreams are themeselves the way we have

already

interpreted the facts.

Bionian thought has led several authors to equate the activity of dream thinking with the

mental activity of waking, emphasizing the function of both of developing, maintaining and

re-establishing the psychological organization of the self and the regulation of affects.

We are close to the procedure that A. Ferro has called «transformations in dreams»,

that is when the analyst mentally introduce the predicate "I had a dream" to the patient's

communication, whatever it may be. This linguistic-cognitive ritual, immediately strips the

external reality of its significance, predisposing the analyst to the “dreamiest” attention

possible.

We are close to the procedure that A. Ferro has called «transformations in dreams»,

that is when the analyst mentally introduce the predicate "I had a dream" to the patient's

communication, whatever it may be. This linguistic-cognitive ritual, immediately strips the

external reality of its significance, predisposing the analyst to the “dreamiest” attention

possible.

Ferro (2013)

supports the need to reconstruct every communication as if it were a dream, and the need for

patient and analyst to dream together.

The dream allows the analyst to work on the patient's alpha function, but also on his own,

through a sort of training in the multiplicity of perspectives that the dream story offers.

Within the analytic field, the dream remains the main monitoring tool, since it represents

one of the most creative ways that the patient has to communicate his analytic experiences.

With Ferro, there are no external, internal or transfert communications that do not belong

to the setting within the analysis and that cannot be considered narrative derivatives of

the dreamlike thought of waking. Even the more subjective elements such as the patient's

dream belong to the field to signify and signal the movements of the waking dream related to

the movement in which the dream is narrated. The field allows you to describe and collect

emotions, clarifying and focusing them, using the characters of the setting, who lose their

historical-referential status, to assume the characteristic of transformative processes of

the analytic couple.

So, finally, Ferro tells us that dreams should not be hardly interpreted: they are the

clearest and simplest story and should be easy to understand. The process of attributing

meaning to the dream, more than its symbolic decoding, can lead to recognizing oneself in

its functioning and bringing out the need to arrive at a new, more complex, identity

reality.